By Frederico Barros

The year was 1960 and Brazilian composer César Guerra-Peixe submitted his Trio, for violin, cello and piano to a contest held by the Brazilian Ministry of Education’s radio station.<1> Click here for the score and recording. On the surface, the piece is illustrative of Guerra-Peixe’s output of the period, but some of its specificities offer interesting points of discussion. From the modal techniques employed and explicit nationalism to the clear structure and tightly-knit thematic work, the Trio shows how Guerra-Peixe positioned himself in the debate about Brazilian music at the time. Some old-school motivic analysis may help us better understand what this means.

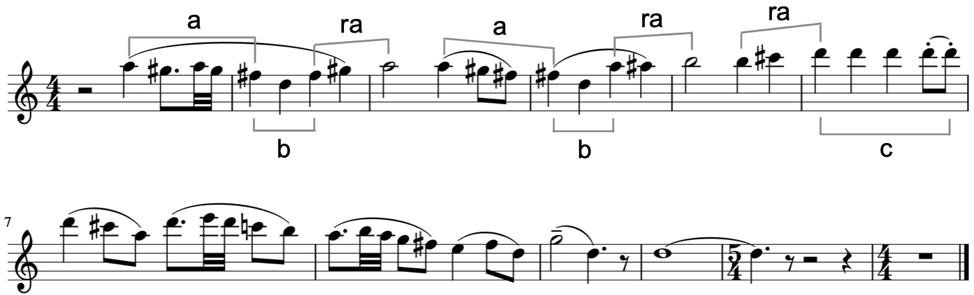

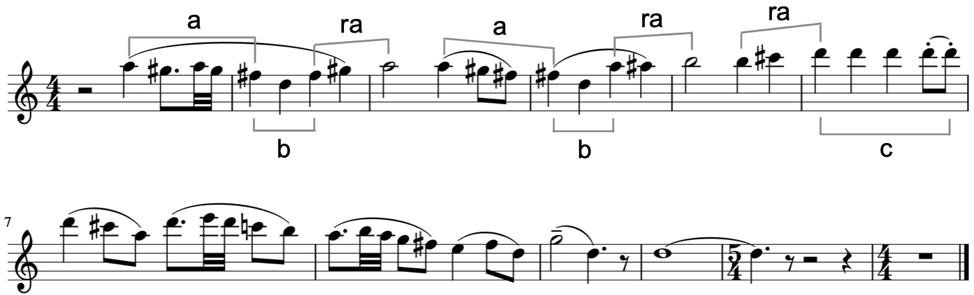

The sonata-allegro begins with the first thematic group’s theme 1 (A1), played by violin and cello two octaves apart and clearly related to the Brazilian northeastern region:

Figure 1: Guerra-Peixe – Trio, 1st mov., A1, m. 1-11, violin part

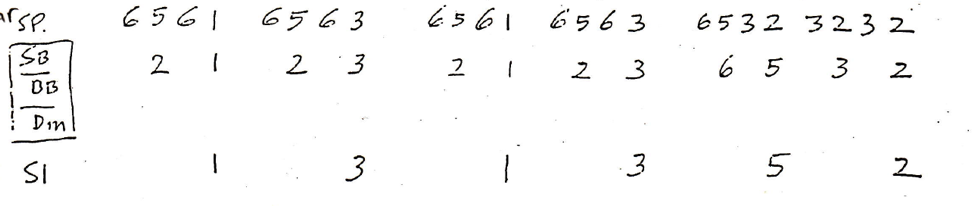

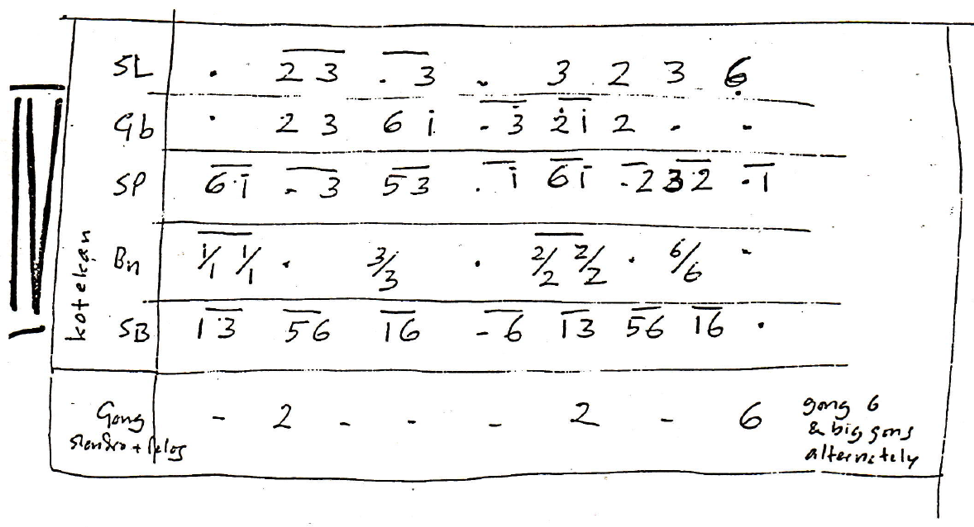

Showing why musical materials are related to a place or human group is a complex endeavor. However, at least in this case, we can let the composer himself speak. In the essay Os Cabocolinhos do Recife,<2> Guerra-Peixe presents examples very similar both to A1 and B2 (figure 5 below).

Figure 2: Examples of Cabocolinhos melodic figures collected by Guerra-Peixe<3>

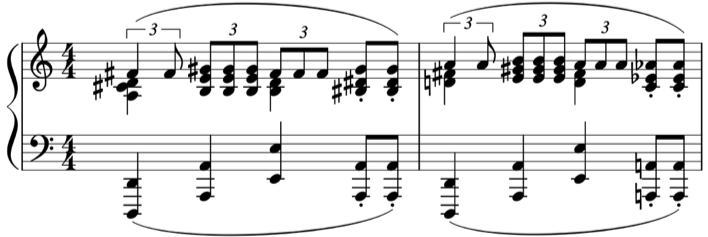

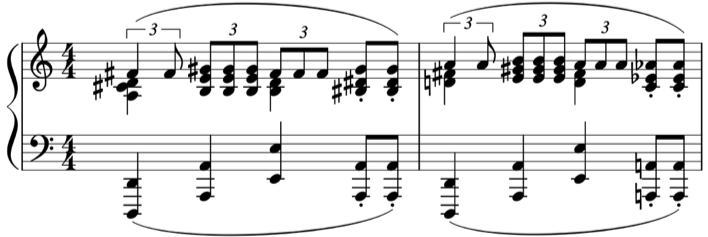

The origin of the piano accompaniment in A1 (figure 3) is harder to trace, but its rhythmic structure, repeated until m. 10, combined with the range of a major second (with some variation) in the highest voice can be convincingly linked to the “elements of the berimbau” that Guerra-Peixe would later say were present in the Trio.<4>

Figure 3: Guerra-Peixe – Trio, 1st mov., A1, m. 1-2, piano part

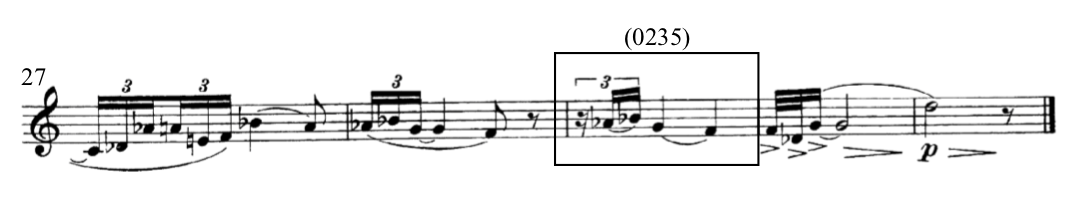

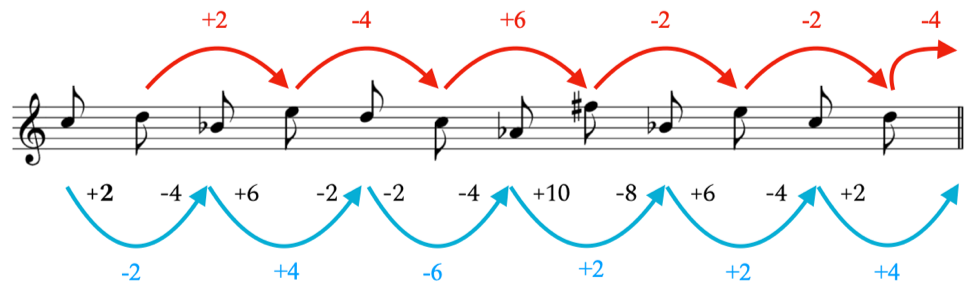

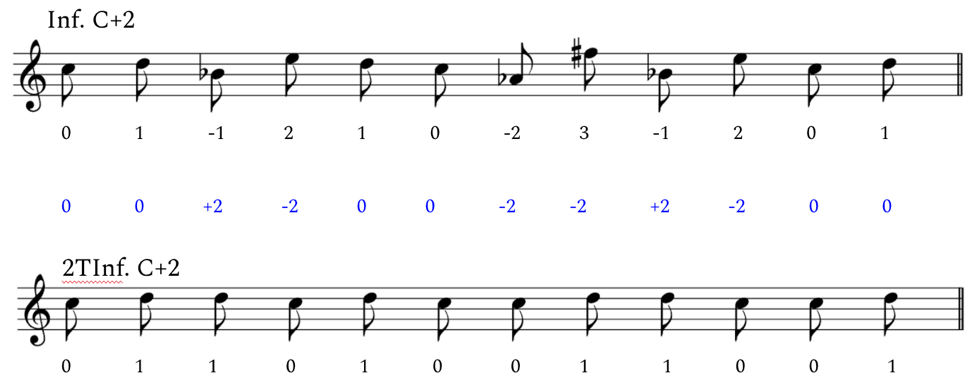

The second theme of the first group (A2), by its turn, is based on the cell c from A1—whose rhythm was also heard in the piano left hand in A1 (as shown in fig. 3):

Figure 4: Guerra-Peixe – Trio, 1st mov. Cell c (from A1) and A2 (m. 26-29)

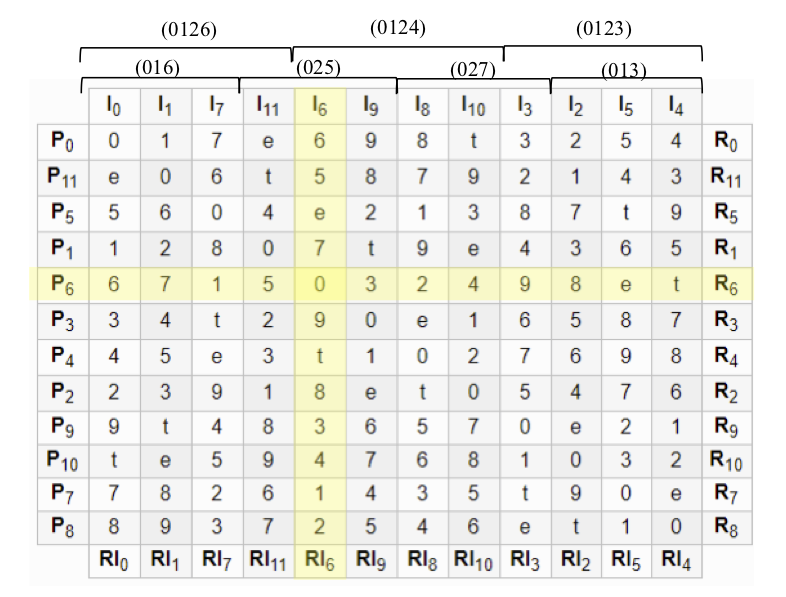

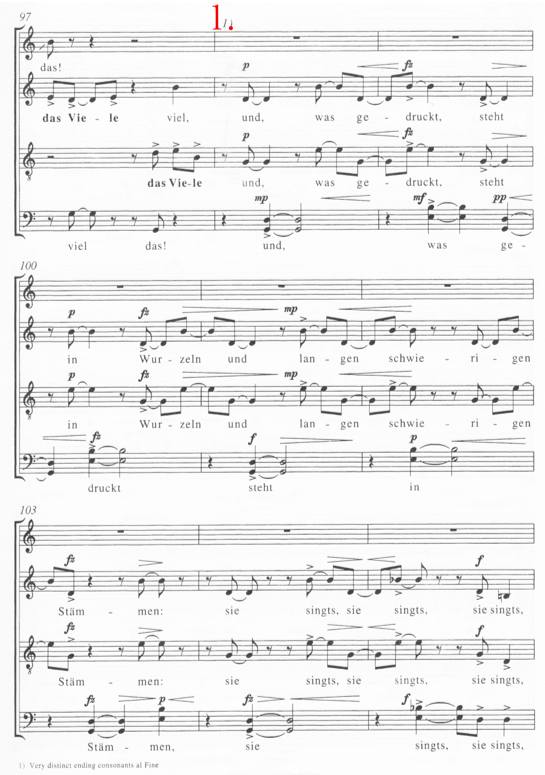

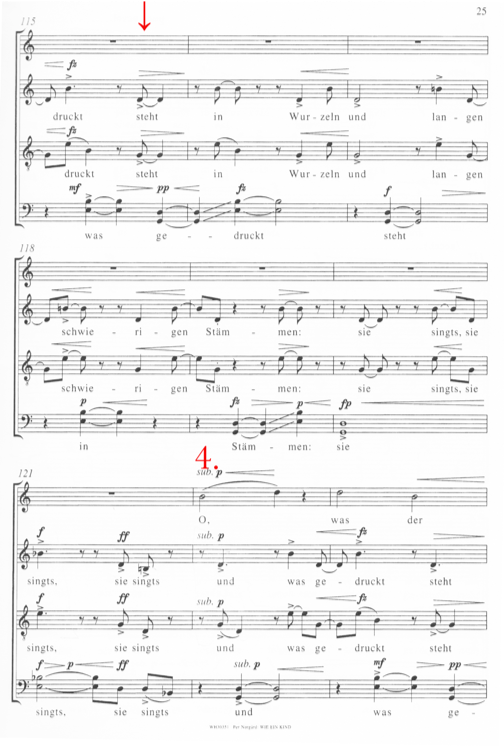

Finally, the piece’s tonal plan goes from D Lydian (A1) to F# Minor (A2), and then to B Dorian on the first theme of the second group (B1). It then reaches A Lydian on the second theme of the second group (B2), the closing theme that brings back the Lydian sound of A1, to which it is clearly related:<5>

Figure 5: Guerra-Peixe – Trio, 1st mov., B2, m. 70-74, piano right hand

From the first group to the second—the foundational polarity of sonata form—the piece descends a minor third, as if going from major to relative minor, but here making a homologous move from D Lydian to B Dorian. Despite B2 being in the dominant region, the modalism present in the Trio takes over the role of the tonal relations in a conventional sonata-allegro. This serves as an entry point into a significant aspect of this piece: Guerra-Peixe stayed rooted in principles from the Western tradition while infusing them with elements of different origins; following sonata procedures by the book, but employing material seen in his time and place as possessing a distinctive Brazilian character.

Some years later, Guerra-Peixe would state that he wrote the Trio in a deliberately academic fashion, hoping it would make it fare better in the contest.<6> Furthermore, the elements indicated above are all fairly common in the Western tradition, usually being considered indicators of good compositional technique, even if somewhat dated. However, these elements tend to be considerably subtler in other works of the composer from the same period, putting the Trio in a somewhat special place in his oeuvre and raising the question of whether we should take all this at face value.

Born in 1914, Guerra-Peixe’s formative years were marked by the rise of the first Modernist generation in Brazil. It was a period of both aesthetic modernization and of coming to terms with the idea of a national art, and throughout the following two decades this two-fold task would converge. In this very same process, the first modernists would oppose those who came before them with charges of eurocentrism and traditionalism, but slowly sliding into being themselves the new established tradition—at least that’s how many of their successors saw them. To add insult to injury, this took place through the participation of many of those modernists in the Getúlio Vargas dictatorial regime.<7> To put it bluntly, during the 1940s younger composers such as Guerra-Peixe tended to see their nationalist-modernist peers as uninteresting, repetitive, and in many cases as actual sellouts.

It was the time when Guerra-Peixe joined the Música Viva group—centered around German composer Hans-Joachim Koellreutter—and got into twelve-tone music, first radically opposing any form of nationalism but then gradually starting to experiment with combining the two trends. His stint with dodecaphony lasted until around 1949, when questions that had been bugging him for a while about who his music could reach and its social utility reached a peak.<8> Guerra-Peixe then plunged both into the Brazilian countryside and in a creative crisis that would eventually lead him to abandon the twelve-tone technique for good in favor of a music that fed heavily from the proto-ethnomusicological researches he had been doing around that time.<9> Having joined the nationalist bandwagon now, he would criticize his new colleagues by turning their own principles against them, with charges of poor knowledge of the country’s traditions and lack of compositional chops.<10>

Figure 6: Guerra-Peixe in 1950

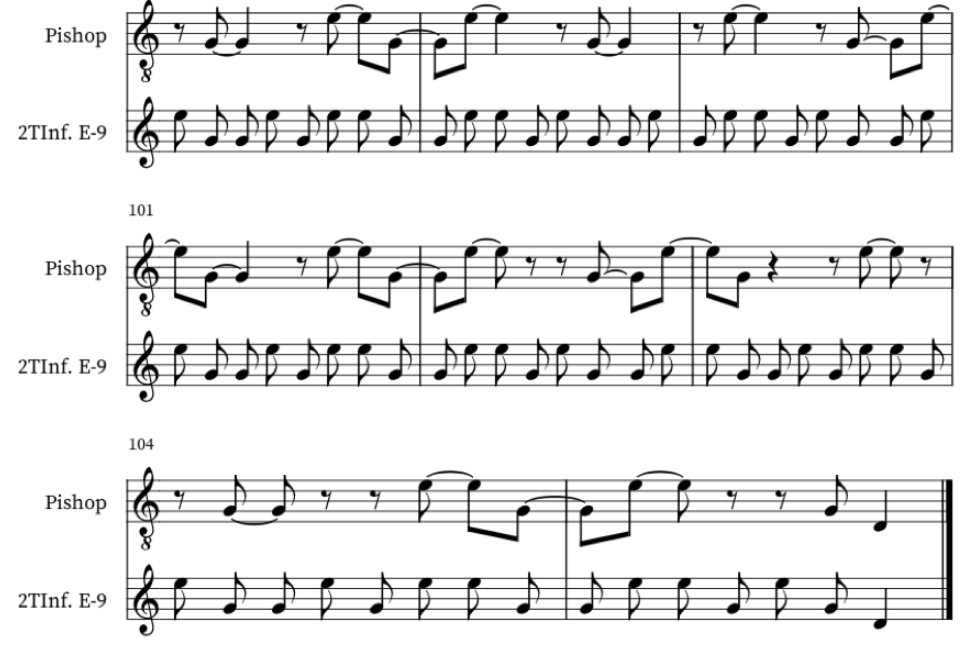

Guerra-Peixe used to show off his knowledge of Brazilian regional cultures by ditching traditional elements of Western music in favor not only of melodic ideas and rhythms—a practice that at the time was common currency for nationalists worldwide—, but also structures, timbres and forms he learned during his countryside excursions. An eloquent example is the first movement of his String Quartet n. 2, from 1958: at first it may seem like an odd sonata-allegro, then one starts wondering if it isn’t a rondo… only to finally, with some luck, find out that the composer employed the form of the cateretê from São Paulo. To make matters even more complicated, we are not dealing with a song form or equivalent, but with something more akin to a sequence of dances or a ritual whose development is mirrored in the piece.<11>

Thus, the meticulous melodic construction and compositional prowess shown in the Trio can be understood as a deliberate act in a very specific sense. Without getting into value judgments, even if Guerra-Peixe may have misevaluated the jury—he received the second prize and the winning piece, by Marlos Nobre, cannot be said to be conservative, after all—, the Trio reveals that he considered them conventional both on aesthetic and technical grounds. It is true that nationalism would bring Guerra-Peixe and the jury together, but he tended to favor (and boast) a more nuanced view of Brazilian music. When we look at the technical side things get even fuzzier, though, as Guerra-Peixe would often also derive procedures from Brazilian folk sources, perhaps risking a relative alienation of an audience more attuned to the Western canon.

That’s much less perceptible in the Trio. We won’t find some alternative form here, but a proper sonata-allegro, and as such the thematic material is orderly presented. While rhythms from one Brazilian state, Bahia, serve as accompaniment to melodic figures from another, Pernambuco, purposefully blurring geographic frontiers, these work in tandem to form a more general, less localized idea of Brazil. Finally, the specific modal elements he resorts to here may sound Brazilian, but below the surface they serve to put very Western structural forces in motion.

This is not to say that elsewhere Guerra-Peixe would always avoid the Western concert music tradition—be it modern or classic-romantic. On the contrary, these are always present in some shape or form, but often transformed: harmony, timbre, developmental procedures, and other aspects of Western musical thinking would be to some extent impacted by the folkloristic investigations he engaged in from the 1950s on. Threading the line that separated his aesthetic demands from the taste of an imagined jury, he ended up exposing some shortcomings of the modernist project he was himself stumbling upon but couldn’t quite fathom at the time, touching on things we are still grappling with today: alternative theories of form, sound, discourse, and drama, amounting to other ways of thinking about music itself which may not even fit in these categories.

Footnotes

<1> Rádio MEC’s II Concurso de Composição Música e Músicos do Brasil.

<2> GUERRA-PEIXE, C. 2007. Estudos de folclore e música popular urbana. Samuel Araújo (org.). Música editada. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG.

<3> Ibid.

<4> Liner notes by the composer for the LP Documentos da Música Brasileira, v.17, LP 356-404-203, MEC/Secretaria de Cultura/Funarte. The berimbau is an instrument mostly associated with the capoeira, from Bahia. It plays two pitches—usually close to a major second in Western theory—that are subject to timbral variations through various playing techniques.

<5> FARIA, A. G. 2000. “Guerra-Peixe e a estilização do folclore.” In: Latin American Music Review. vol. 21, no. 2.

<6> See note 4 above.

<7> SCHWARTZMAN, S., H. M. B. BOMENY, V. M. R. COSTA. 2000. Tempos de Capanema. São Paulo, SP: Paz e Terra: Editora FGV; SQUEFF, E., J. M. WISNIK. 2004. Música. São Paulo, Brasil: Editora Brasiliense.

<8> It’s worth mentioning at this point that the Second International Congress of Composers and Music Critics took place in Prague, Czechoslovakia, in 1948 and brought many of the Socialist Realism directives to music. Its influence was strongly felt in Guerra-Peixe’s circle of relations, as Claudio Santoro, one of his colleagues in the Música Viva group, attended the congress as a delegate of the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB).

<9> See ARAÚJO, S. “Introduction” (GUERRA-PEIXE 2007); ARAÚJO, S. 2010. Movimentos musicais: Guerra-Peixe para ouvir, dançar e pensar. Revista USP, (87), 98-109. USP.

<10> For a detailed discussion, see BARROS, F. César Guerra-Peixe: a modernidade em busca de uma tradição. Doctoral dissertation. Departamento de Sociologia. São Paulo, Brazil: Universidade de São Paulo. 2013.

<11> FARIA, A. G. 2007. “Modalismo e Forma na obra de Guerra-Peixe” in: FARIA, A.G.; BARROS, L.O.C.; SERRÃO, R. Guerra-Peixe: um músico brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: Lumiar.

Frederico Barros is Music History professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. He has a PhD in Sociology and MPhil and BA in History. Research interests include concert and urban popular musics and arts during the 20th and 21st centuries, modernism, and nationalism.

https://fredericobarros.com